CPS says risky play crucial for child development, experts urge embracing outdoor adventure

Thank you to Sarah Forrest, second year journalism student at Carleton University, for providing this post.

Outdoor risky play is key for childhood development, says Canadian Paediatric Society, but it’s not quite so simple.

In a statement released on Jan. 25, CPS defined risky play as “thrilling and exciting forms of free play that involve uncertainty of outcome and a possibility of physical injury.” This may include playing at heights, playing at speed, play involving tools, play involving potentially dangerous elements, rough and tumble play, play with risk of getting lost, play involving impacts, or vicarious play. A list examples can be found below:

| Categories | Examples |

|

Climbing, jumping, balancing at height |

|

Bicycling at high speed, sledding, sliding, running |

|

Supervised activities involving an axe, saw, knife, hammer, or ropes (e.g., building a den or whittling) |

|

Playing near fire or water |

|

Wrestling, play fighting, fencing with sticks |

|

Exploring play spaces, neighbourhoods, or woods without adult supervision, or in the case of young children, with limited supervision (e.g., hiding behind bushes) |

|

Crashing into something or someone, perhaps repeatedly and only for fun |

|

Experiencing the thrill of watching other (often older) children engaging in risky play |

List adapted from the Jan. 25 Canadian Paediatric Society position statement on risky play

Each type of play looks different for children of different ages and abilities, but experts say the benefits for all children cannot be understated. “Play provides an opportunity to interact with peers and develop social skills, and it allows them to develop muscular strength and cardiovascular fitness,” says Dr. Maeghan James, a postdoctoral fellow with the CHEO Research Institute. Dr. James holds a PhD in kinesiology, and her current research interests include promoting inclusive outdoor active play for children of all abilities.

The CPS report also notes that risky play can have positive impacts on children’s mental health, “Risky play helps facilitate children’s exposure to fear-provoking situations, providing them with opportunities to experiment with uncertainty, associated physiological arousal, and coping strategies, which can significantly reduce children’s risk for elevated anxiety.”

What happens when children don’t have these experiences?

Some experts even think that a lack of risky play, and outdoor play in general, is a contributing factor to the current mental health crisis. If children are not given the chance to learn how to safely manage situations where there is a possibility of risk, the effects can last into adolescence and adulthood. “When we raise a whole generation of children, where we have completely bubble-wrapped them, they are never given that opportunity. So when they then grow up and are expected to live independently, in the real world, and are exposed to real, actual risks, they’ve never learned how to deal with that,” says Dr. Louise de Lannoy, executive director of Outdoor Play Canada. Dr. De Lannoy also holds a PhD in exercise physiology. Her work with Outdoor Play Canada primarily focuses on promoting, protecting, and preserving access to play in nature and the outdoors for all people living in Canada.

Traditional playground structures are typically the “go-to” when it comes to outdoor play. (Image by Sarah Forrest)

But what about safety?

Popping the bubble wrap and letting children take risks can bring about sentiments of fear and anxiety.

Lewis Smith, manager of national projects at the Canada Safety Council had some concerns with the wording of the report. “Taking risks is one thing, taking calculated risks, being fully aware of the potential hazards that could come into play is another entirely,” he said. Smith noted that he was concerned when he first heard that CPS was “encouraging people to take risks”. However, after reading the report himself, he understood the benefits of this type of play. Smith’s initial feelings of concern echo those of many parents and childcare professionals.

“I think that [those] feelings really come from worry and uncertainty about whether or not the child is going to be able to manage those risks. And that’s a really uncomfortable place to be because, you know, we have to give them opportunities to learn how to manage risk, but at the same time, as an adult, it’s our job to make sure that they stay safe,” says James.

CPS also notes that “Risky play does not involve ignoring safety measures, leaving children unsupervised in hazardous areas, or pushing children to take risks outside their comfort levels”. Experts say it’s all about managing the line between risk and hazard.

How can parents manage feelings of fear?

One recommended strategy is to use language that is instructive, but also gives autonomy and independence to the child. Examples of this can be found below:

|

List adapted from the Jan. 25 Canadian Paediatric Society position statement on risky play

Experts do note that learning to use this language is easier said than done.

“That takes a lot more effort than saying be careful. Be careful is a sort of an automatic response. And so it is hard, but it’s a good exercise in communicating with the child and it is a good exercise in fostering independence of that child,” says Dr. de Lannoy. The idea with this strategy is to allow children more autonomy so that they can learn from their experiences, without mom or dad hovering over their shoulder. Rather than keeping children as safe as humanly possible, CPS recommends keeping them “as safe as necessary,” when engaging in risky play.

Where can children participate in risky play?

In order to engage in risky play, you need access to spaces that allow for it. For most, this means playgrounds and parks. But for children who have other factors at play, such as financial struggles, access to these spaces isn’t always so easy. Families in low income situations can typically rely on play structures at school, where children are supervised by educators and can engage in risky play while their parents are at work. However, children attending the W.E. Gowling Public School in Ottawa are currently facing the loss of their play structures which takes this option away.

W.E. Gowling – Does a school without a play structure have to be a school without play?

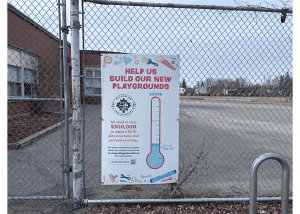

A sign posted outside the school grounds at W.E. Gowling, asking the community for donations to rebuild their playgrounds. (Image by Sarah Forrest)

“The kindergarten structure had been anticipated to be retired, given its age. The other play structure is the unfortunate situation where it had been expected to last a few years longer, but the structural integrity inspections led to the early retirement decision,” writes OCDSB Board Trustee Matthew Lee in an email. However, the Ministry of Education does not recognize play structures as ministry funded infrastructure, meaning all of the fundraising to rebuild these parks falls on the school community. The kindergarten structure coupled with the early retirement decision of the other playground leaves the school community responsible to raise $300k. The funds have been raised to rebuild the kindergarten structure, but the other is set to be removed with no replacement in sight.

A sign prohibits the use of the set-to-be-removed play structure at W.E. Gowling. (Image by Sarah Forrest)

“Gowling is situated in one of the city’s lower economic status neighborhoods. The ability to replace two structures is not within the community’s capability at this time,” said Lee.

So, what to do with the empty schoolyard?

In the meantime, there are other options, the community might just have to think outside of the box. According to Dr. de Lannoy, there are benefits that come from bringing natural elements into the play space, such as wooden logs or discs. Not only are they cost effective and sustainable, but they also encourage creativity. “All of those pieces are supportive of active and more risky play,” she said.

The pen that once hosted the kindergarten play structure, now an empty sandpit. (Image by Sarah Forrest)

The sandpit that used to house the kindergarten play structure may seem bleak to some, but James views it as a world of opportunity. Adding components like stumps or logs that children could climb over could add that missing element of risk that the playground once provided. “We can support imaginary play, but also play that’s going to allow them to use their bodies and try new skills and balance on things and jump over things,” she said. Both Dr. James and Dr. de Lannoy urge parents and educators alike to rethink their traditional perceptions of the spaces in which play can occur. “There’s a whole kind of downward trend when you don’t have access to play. Does that mean that you need to have a manufactured play structure for all of this to happen? Not necessarily,” says Dr. James. Shifting the perspective from a basic slide and swing set to natural elements, can help make outdoor risky play more accessible, allowing children to reap its benefits.