The role of nature-based early childhood education on children’s physical, social, emotional and cognitive outcomes

Thank you to Dr. Avril Johnstone, Dr. Anne Martin, and Dr. Paul McCrorie, from the Social and Public Health Sciences Unit, University of Glasgow, Scotland, for providing this post.

What is nature-based early childhood education and why is it important?

“I like being outside with my friends, I like all the colours outside and all the space. We make shelters and we make up different games, like getting trapped on an island, or being on a boat and making our escape! I like doing science outside too – like different experiments, especially when the sun is out.”

Taken from a child attending nature-based early childhood education (ECE), this quote encapsulates what this type of early years provision is all about – being outside, playing with friends and having fun! Nature-based ECE, perhaps more commonly known as forest kindergarten or nature-based preschool, is a popular and burgeoning type of ECE characterised by an environment rich in diverse natural features in which children spend most of their day outdoors interacting with these elements through play. Natural features could include trees, vegetation, hills, rivers or ponds, and other natural materials. This contrasts with traditional ECE which is more common practice and is typically characterised by children spending most of their day indoors and when they are outdoors the playground consists of mostly man-made features.

So why are we interested in nature-based ECE in particular?

The early years is a time of rapid development in childhood where children are shaped by the early experiences they have with their surrounding environment. One hugely influential environment where young children spend a large portion of their day is ECE settings. Generally, we have good knowledge on how ‘traditional’ ECE practice supports childhood development across a number of outcomes, however, what remains unclear is the role of nature-based ECE on childhood development, with research exploring its impact still in its infancy.

It is thought that nature-based ECE may provide additional benefits beyond the norm as children spend more time outdoors in an environment rich in natural features. We know that exposure to nature such as local parks or beaches are important for human health, particularly in reducing stress, increasing physical activity levels and improving mental health outcomes. Furthermore, in nature-based ECE, the potential richness and diversity afforded by the environment can enable children to engage in a range of play types using different natural elements for extended periods of the day, which may impact important outcomes such as physical activity, motor competence and social skills.

Given the potential for nature-based ECE to improve childhood health outcomes, we conducted a novel and comprehensive search of the literature to synthesise findings on the role of nature-based ECE on children’s physical, social, emotional and cognitive outcomes.

How we answered this question.

We searched nine research databases as well as websites and university theses for documented work on the role of nature-based ECE on children’s physical, social, emotional and cognitive outcomes. We compiled major findings related to our outcomes of interest (i.e., children’s physical, social, emotional and cognitive health and wellbeing) and assessed the quality of the evidence to ensure confidence when interpreting the findings.

What we found.

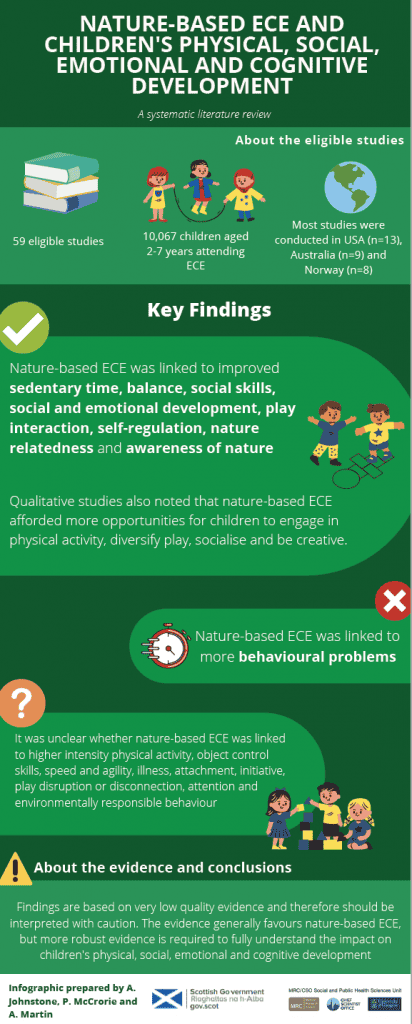

We identified 59 studies that met our pre-defined criteria, and published our findings as two systemic reviews, with one exploring the physical benefits of nature-based ECE and the other exploring the social, emotional and cognitive development benefits. The total sample size was 10,067 children aged 2-7 years with most studies conducted in the USA (n=13), Australia (n=9), Norway (n=8) and Canada (n=5).

We found that nature-based ECE had some benefits across a number of outcomes. For example, there were links to reduced sedentary time, and improved balance, social skills, social and emotional wellbeing, play interaction, self-regulation (ability to understand and manage behaviour), nature relatedness and awareness of nature. However, nature-based ECE was linked to more behavioural problems and it was unclear whether nature-based ECE was linked to higher intensity physical activity, object control skills, speed and agility, illness, attachment, initiative, play disruption or disconnection, attention and environmentally responsible behaviour.

Furthermore, qualitative studies, which used observational and interview methods, gave further insight into why nature-based ECE may impact these outcomes. Findings noted the importance of the natural environment in affording opportunities for children to diversify their play which enables them to engage in physical activity, socialise and be creative.

Take home messages.

It is important to note that the findings are based on very low-quality evidence meaning that we must interpret them carefully. To fully understand the role of nature-based ECE on children’s health and development, we need to:

- Raise the quality of the studies by having larger sample sizes, including control groups and using robust measurement tools to measure outcomes pre and post engagement in nature-based ECE;

- Describe the duration and quality of nature to tell us how many hours or days children need to spend in nature-based ECE to get optimal benefits on health outcomes;

- Measure outcomes over a longer period (2+ years) to tell us whether any potential benefits are sustained as children mature.

Although the evidence generally favours nature-based ECE, by improving the quality of the research we will be able to understand whether nature-based ECE is better than, or equal to (or potentially lesser than) traditional ECE and thus develop more specific recommendations for policy and practice in the future.

What is next?

Our research priorities are characterised by the three key gaps in knowledge identified above. We will endeavour to develop more robust and rigorous evaluation designs that will answer the most pressing research questions from our stakeholders. These will include informative studies that i) explore what the ‘optimal’ time spent in nature-based ECE is; ii) unpack the issue around defining what ‘quality’ outdoor spaces look like; and iii) investigate the relationship between time and quality as it relates to health and well-being outcomes. Where possible, we will also try to identify current longitudinal datasets and/or explore opportunities where we can follow young children, starting in ECE, through the education system so as to evaluate long-term benefits of nature-based ECE.

Read the full systematic review on nature-based early childhood education and children’s social, emotional and cognitive development here.

Read the full systematic review on nature-based early childhood education and children’s physical activity, sedentary behavior, motor competence and other physical health outcomes here.

Dr. Avril Johnstone is a research associate within the Places programme at the MRC/CSO Social and Public Health Sciences Unit, at the University of Glasgow, Scotland. Her primary research interest is in the role of active and outdoor play on children’s health and wellbeing.

Dr. Anne Martin is a research fellow with the Complexity in Health Improvement Programme at the MRC/CSO Social and Public Health Sciences Unit, University of Glasgow, Scotland. Her work focuses on evaluating and developing complex public health interventions.

Dr. Paul McCrorie is a research fellow at the MRC/CSO Social and Public Health Sciences Unit, University of Glasgow, Scotland. Paul is the lead researcher on the Studying Physical Activity in Children’s Environments across Scotland (SPACES) study in which he is investigating the role of the built and natural environment and local neighbourhood on children’s health and physical activity levels and behaviours.

Featured image by Jess Zoerb on Unsplash